The big buck and his does burst from the thick cover of greenbriar and cedar trees. The deer dashed at top speed across a nearby field, white flags waving. The afternoon sun flashed off the shiny, wide rack. My cousin and I stood in awe watching as they disappeared over the crest of a nearby hill. It was early autumn and my cousin and I found ourselves wandering in the woods on the family farm. After the deer departed, we chatted excitedly about how big and beautiful the buck was. We dove into the cover they had evacuated examining the evidence left behind. The greenbriar shredded our skin and clothes but we wanted to soak up everything we could learn about the giant buck and his girlfriends. I was so excited about this encounter that I went home that night, found a fresh notebook and started a journal about the sighting.

In 2025 my cousin and I would have probably been disrupting someone’s afternoon hunt. But this was circa 1975. Deer hunting in South Jersey was more of a novelty then. Something one did late in duck season. Sure, there were a few traditional archery enthusiasts who took to the woods with a bow but the likelihood of any such person being in the farm woodlot that afternoon was pretty slim. The encounter with the buck planted a seed.

I never knew I wanted to be a hunter. In fact, it almost didn’t come to be except fate intervened. I began life in a rural house out in the country with 60 acres of paradise out the back door. At some point in second or third grade, my Mom decided my brother and I needed to be around more kids, better schools, and more community. We put our country house for sale and moved to a more suburban area with neighbors, “blocks”, and community events. The house in Elsinboro sat on the market for a couple years and almost sold until the potential buyer’s daughter reacted poorly to the mosquitoes that were ever-present in Elsinboro. At some point, we sold our suburban home and, thankfully, moved back to Elsinboro. Once again I had paradise out the back door.

Still, the hunting seed itself didn’t really set in until I accompanied Dad on a rainy October morning. After spending time on some clay targets, and helping build a duck blind Dad put a Savage 20 gauge single-shot in my hands and sat me in a duck blind. The rest, as they say, is history.

Duck hunting was a way of life in South Jersey. It is what people did in the fall. But the big buck encounter had stirred something inside me. That seed the buck sighting planted that fall afternoon germinated and grew to the point that thoughts of deer and bucks began to pervade my waking moments. Dad had little interest in deer hunting though he and Mom had spent some time on stand occasionally. I bugged Dad perpetually about it. He finally relented and built a very fancy deer stand in a likely spot. The stand featured safety rails, and entry via a trap door. Aside from that, Dad didn’t really know much about deer hunting. In hindsight, the little bit of time we spent on stand together was a bit of a waste as far as deer hunting though it was some really high-quality father/son time. I would have to wait until I could hunt on my own to be a successful deer hunter. I’d also have to figure it out myself.

In the 1970s we didn’t have the internet, YouTube, or Wiki to learn things. To figure out how to hunt deer meant reading books, magazines, and talking to the few people I knew who hunted deer a lot. It meant seeking out those who had actually killed deer. (There weren’t that many back then.) But mostly it meant getting out in the woods and learning. I watched deer. I followed deer. I studied the places deer had been and learned how to tell fresh sign from old sign. I watched where deer were going to figure out what they liked for food and habitat. I quickly realized to be a successful deer hunter meant spending as much time as possible in the woods even when it wasn’t hunting season.

Back then (and even now) New Jersey had a very short firearms deer season. It was 6 days running from Monday to Saturday. E-V-E-R-Y-O-N-E took Monday off from school to hunt. Well, at least all of the country kids. There were some humorous moments courtesy of our inner city school principal who hated the fact that the country kids weren’t in school one Monday a year. He spent his day reporting us. I wish I was home when my Mom “talked” to the truant officer.

That 6 day firearm season came and went pretty quickly and a couple unsuccessful seasons led me to two conclusions: 1) I needed to learn more about deer 2) I needed to be able to hunt more. The answer to part 2 was obvious. I needed a bow to be able to hunt the month-long archery season. Certainly with a full month in the woods, success would come! Little did I know at the time how difficult bowhunting could be. Still, the campaign for a compound hunting bow began.

The campaign mostly stalled until I leveraged boyhood trauma against my mother. At an early age I was diagnosed with severe scoliosis. Visits to the Alfred I. Dupont Institute in Delaware led to the conclusion that I would spend my remaining days of youth wearing a hard, plastic Wilmington brace to straighten my body as I grew. It sounded like torture and in a way it was. But that didn’t stop me from playing on my Mom’s guilt. On the way home, I convinced her to stop at a local archery shop. I was shooting my new compound bow later that afternoon.

With my new bow in-hand, I redoubled my efforts to learn about deer, scout the best spots, and spent time nearly every day flinging Eason aluminum arrows at compressed straw bales in the back yard. Sometime around 1980 I finally found success in the deer woods. Like many, my first was a button buck I killed with my bow on my cousin’s farm. The little deer died in sight from my rickety tree stand and I practically fell to the ground in my haste to lay hands on it. Since then I have been fortunate to take a couple hundred more deer mostly with a bow though these days I am a bit choosier when it comes to the quarry.

Since moving to Pennsylvania, I have been blessed with good hunting friends and been fortunate enough to become part of a traditional Pennsylvania deer camp. Our physical camp location has moved a couple times and we are now based out of the Poconos with the same core of people. Moving locations from central Pennsylvania to northeast Pennsylvania meant learning all new places to hunt. There was no google search to show us good spots and no phone app to tell us where to go. It meant, putting boots on the ground and spending hours scouring the vast quantities of public land available to find likely spots to be successful.

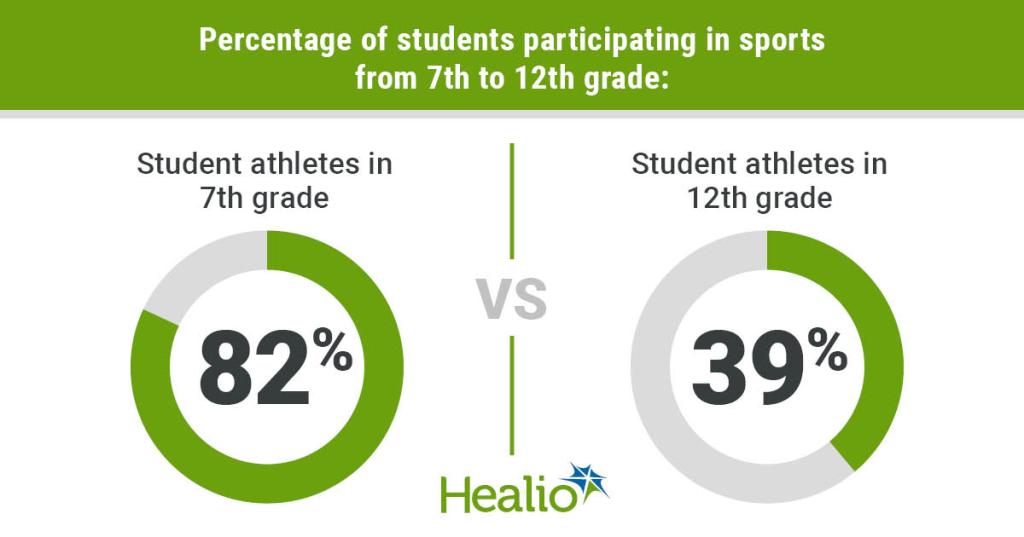

Participation in hunting and hunting license sales have been declining precipitously across the USA for many years now. While some think hunting is barbaric and welcome such news, I don’t think anyone is prepared to replace the money hunters sink into conservation. For this and a variety of other reasons I do my best to help new hunters get started. But often times, here is where things take a turn and we have to ask why young people are not taking up hunting.

When I am approached by someone who says they or their child want to learn to hunt, I ask the question “Do you want me to teach you how to hunt or do you want me to guide you to a deer to kill?” Whether most admit it or not, what they really want is to be guided to a deer. There isn’t interest in the time commitment needed to learn to be a successful hunter.

There is, what I feel, a misconception in the hunting community. We have this notion that if we get a child in the woods and get a deer in front of them they’ll be hooked for life. To that end, we show them the basics of how to shoot a rifle or crossbow. We then wake them up opening morning, pack their stuff in our bag, along with an iPad or phone for gaming to ward off boredom. There is also plenty of snacks and hot chocolate. All things to keep the young shooter occupied in hopes that a deer comes along. Ideally, life in the wild plays out like a video game and the wait isn’t too long. If it is, the youngster is generally allowed to take a nap, play on a device, snack and otherwise be distracted until told to get ready to shoot or that it is time to pack up and get to soccer practice.

If the above sounds a bit cynical it is. I have seen that model applied countless times and the end result is a child who is no more interested in hunting after the experience than before. This tends to be the case whether they get an animal or not.

Us children of the 70s and 80s were the last generation to be set loose on a regular basis. We were literally thrown out of the house after breakfast and told to be home in time for dinner. Whether that meant we were in school and then doing chores or were just out in the wild all day exploring, having fun, nearly dying doing something stupid . . whatever. Did that mean our parents didn’t love us or care about us? Of course not. It meant we were growing as people and learning to make our own decisions. It also meant we had free rein and free time to explore the natural world around us. It meant we could develop our own passions and interests rather than have those “interests” dictated to us by well-meaning parents.

Come the 1990s and later, we had the advent of the helicopter parent and the notion that children always had to busy and supervised. Suddenly, kids were signed up for more organized activities than one should ever try to fit in a lifetime. Each kid went from school to one or more school practices, then some sort of non-school related activity, then homework, then bed. Never was there time to be a kid. Never was their time to get muddy while catching tadpoles or get cut up and bloody crawling through a blackberry thicket after a rabbit. No more were kids given an air rifle and told “don’t shoot anyone” and sent out the back door. Suddenly everything that wasn’t an organized activity required adult supervision at all times lest the child make a mis-step and get hurt or disappointed.

Boy . . that really is some cynicism. But I’m so glad I grew up when I did.

This is germane to the topic though. If a child expresses interest in hunting, it must be squeezed in among a 1/2 dozen other activities. Maybe a quick trip to the rifle range to shoot a gun once or twice before the season or a backyard session at a friend’s house to shoot a crossbow a couple times. (Both of these scenarios are VERY insufficient if one is planning on flinging live ammunition of any kind at an animal.) And equally important, typically an interest in hunting means one thing and one thing only: DEER HUNTING. For some reason, we seem to feel the best way to start new hunters off is with, quite possibly, the most boring form of hunting. 99% of the time a new hunter is probably not going to see a deer. Somehow hunting has become synonymous with deer hunting.

The idea of small game hunting has fallen by the wayside. There aren’t really wild pheasants in Pennsylvania anymore. Hunters must rely on stocked birds that really aren’t a lot brighter than barnyard chickens. But there are plenty of squirrels and rabbits out there. Both of those species are great for teaching hunting basics and have a high degree of success. I can’t imagine better training for deer hunting than sitting in an oak grove, .22 rifle in hand, waiting for the first bushy tail of the morning. There is also abundant waterfowl and migratory birds. Dove hunting is fast and furious, done in warm weather, and is fabulously entertaining yet few new hunters dive into this awesome sport. Back on that youthful duck hunt, it was cold, and rainy and ducks zipped about all morning. It was awesome and I was hooked!

Jumping past the apparently ridiculous notion of new hunters focusing on easier game, let’s return to my question about learning to hunt or being guided to a deer. If one truly wants to be a successful hunter, then hunting has to be as important of an activity as band, soccer, football, or any of the other activities that occupy a young person these days. Too often do we see the newest hunters arrive in camp late on the eve of the hunt expecting to be taken to the best spots. The same hunters exit early to get home for some other activity. Never is time made for scouting. A general rule of thumb is one should plan to spend twice as much time scouting as actually hunting. This is a conundrum when hunting is shoe-horned in between other, more favored activities.

I’ll go the range and help a new person learn to shoot whatever weapon they’ve chosen. I will happily make time to walk the woods and share the knowledge of game I’ve acquired over the years. I’ll help hang a stand. I’ll give my best advice on where to look for good sign. Tomes have been written on white-tailed deer, their lifecycles, their habits, and the best ways to hunt them. I’ve read millions of lines of such material and accumulated some 50 years of my own knowledge I’m happy to share if asked. But honestly, I’m no longer interested in being a guide for someone that wants to fill in a deer tag and say “I got a deer!” There are plenty of professional guides and outfitters out there for that.

I don’t want to sound unwelcoming. In fact, just the opposite. I am delighted to teach a new hunters the things I had to figure out on my own. It would have been so much easier to get started and find success with more guidance.

Unfortunately these days most kids don’t have a wild paradise out their back door even if they were allowed to roam by themselves. That makes the commitment to the idea of being a hunter all the more important. Parents spend endless hours shuffling kids to various practices and sitting on the sidelines while they play. Hunting and the outdoors provides the perfect opportunity to get outside with an excited child and spend time together exploring.

Likewise time at the range needs to be prioritized. Going once and shooting Uncle Ed’s deer rifle off the bench a couple times is insufficient. Should the novice hunter be fortunate enough to get a shot, he or she will be flinging a lethal projectile at a living, breathing animal. Missing is disappointing, but wounding and not recovering an animal is (or at least should be) heartbreaking. That animal was having a pretty good day until shot at. We have a responsibility to take our game as quickly and humanely as possible. This same requirement remains for small game too. Whatever the chosen weapon and quarry, the new hunter should become intimately proficient with the appropriate weapon. The bonus is that range time is fun!

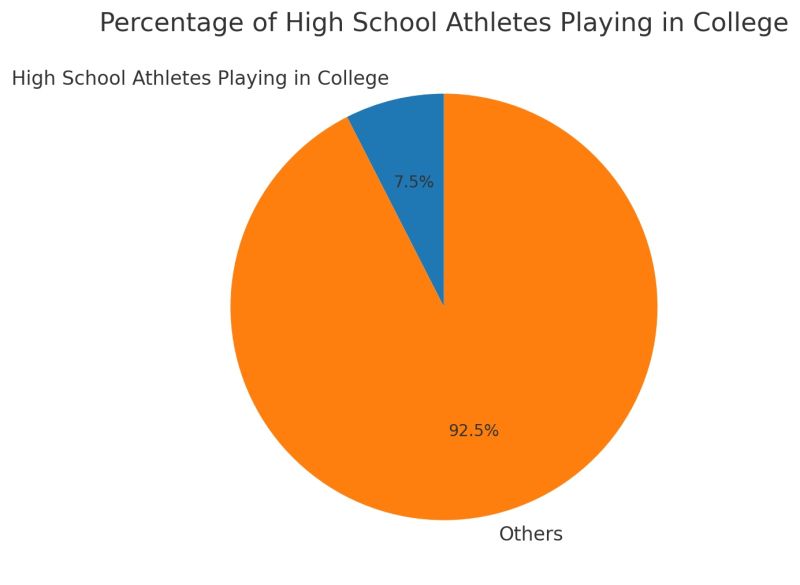

Still skeptical? Well, consider that less than 7% of high school athletes participate in their sport beyond high school. By comparison, hunting is a lifelong activity. I’m not telling anyone to go quit their high school sport if they are passionate about it but if you really want to be a hunter just know you get out of the sport what you put in to it.